Kwentong Migrante

Two immigrant workers' stories revealed from behind their employer's trimmed lawns and spotless streets

On most days of the week, Elle and Lisa work as domestic helpers, residing in the homes of wealthy families in Beverly Hills. Like the majority of workers who labor to upkeep the pristine appearance of this neighborhood, the stories of Elle and Lisa remain at the margins—hidden behind trimmed lawns and spotless streets. In the summer of 2019, Elle and Lisa moved to Los Angeles with their employer, by way of the Middle East.

E: “We were working as nannies for [three] children. We organized their belongings, fed them, bathed them, did at [dito sa U.S.], walang their laundry, played with them, took care of them when they were sick, and put them to sleep. Whether we were in the Middle East or [in the U.S.], my work did not change [nor did the family’s] treatment toward us as their nannies. [The kids would] spit on me, stick their fingers in my face, punch me in parts of my body. They don’t have respect, because their parents are also like that... [Some- times their parents would] say that I am ‘brainless’, ‘an animal’, ‘stupid’... I don’t see their concern for domestic helpers like us.”

This wasn’t the first time Elle or Lisa worked abroad. Prior to this job, both Elle and Lisa worked multiple temporary contract-based jobs as domestic workers throughout the Middle East. They are among two million Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs) in the region. All in all, an estimated 10.2 million Filipinos are working overseas in various countries across the globe.

L: “I first went to Kuwait for two years after which, I went home to see my children. I wasn’t able to save anything, so I returned to the [Philippine recruitment] agency. [For 12 years,] I [worked in] Jordan as a domestic worker... After a contract would end, I returned to the Philippines, only to re-apply again. I worked in Qatar, and then, Bahrain, which was very hard. No days off, no vacation, and my employers weren’t nice to me. One time, I got in a bicycle accident and thought I broke my hand. They wouldn’t let me go to the hospital for an x-ray. They just gave me pain medication.”

Throughout her youth, Lisa worked as a domestic helper for families that her parents owed money to, traveling between her home island of Mindanao and Manila for work. Even with many years of experiencing serious hardship and maltreatment, Lisa maintains an optimistic charm with a personality as vibrant as her dyed red hair. Beneath her funny jokes and quirky exterior, however, glimpses of Lisa’s fighting spirit can be seen as she retells her story.

L: “[My employer] never gave me my wages until I asked for it. Their kids [would] hurt me and my fellow domestic workers. When we asked their parents to talk to their children [to treat us with respect], their parents got mad at us. When they took me to the U.S. for their vacation, they made me lie to the Embassy and say we were getting paid a standard amount... While in the U.S., [my employer’s] driver ran away and they accused us of helping him. I was afraid of what they’d do to me, so I also left.”

E: “In the Philippines, I sold vegetables in the market, but it was not enough to support our growing family. I worked my way up in the garment industry to become a sewing machine operator. In a good month, I made P3,000 or $60 a month until the company shut down. I returned to my vegetable cart, where I was harassed by police [and] endured the heat, cold, and hunger. Even then, there were times when nobody was buying. It was a difficult life, so I decided to look for work outside the country.”

For OFWs like Elle and Lisa, the Philippine government and media tycoons like ABS-CBN deliberately campaign to paint them as the “Bagong Bayani” (new heroes) of the nation, because of the level of sacrifice and struggle they endure to improve the lives of their families and the situation of the Filipino people as a whole. By framing the suffering of OFWs as an expression of duty and heroism, the Philippine government effectively minimizes its critical responsibility to providing jobs and economic stability for its own people. In actuality, the strength of the Philippine economy is attributed partly to the significant contributions of OFWs, whose remittances make up about 10 percent of the country’s economy.

In other words, the Philippine government and their partnering recruitment agencies rely on the export of Filipino labor as a critical money-making scheme for the country. Under these circumstances, profit is more valued than the Filipino people who labor endlessly to create that profit. As of 2018, the total overseas remittances peaked at $28.9 billion or P1.5 trillion—the highest in Philippine history. In the same year, P36.91 billion was collected from 1.3 million migrant workers, while only P1.2 billion was allocated to OFW services—only three percent of what is collected from migrants and less than one percent of total remittances. In addition, OFW applicants are burdened with P27,450 in fees for SSS, Philhealth, and so on.

E: “It was only here in the U.S. that I realized that my fellow domestic workers and I were victims of human trafficking. We were deceived since the very beginning, starting with the recruiting agency.”

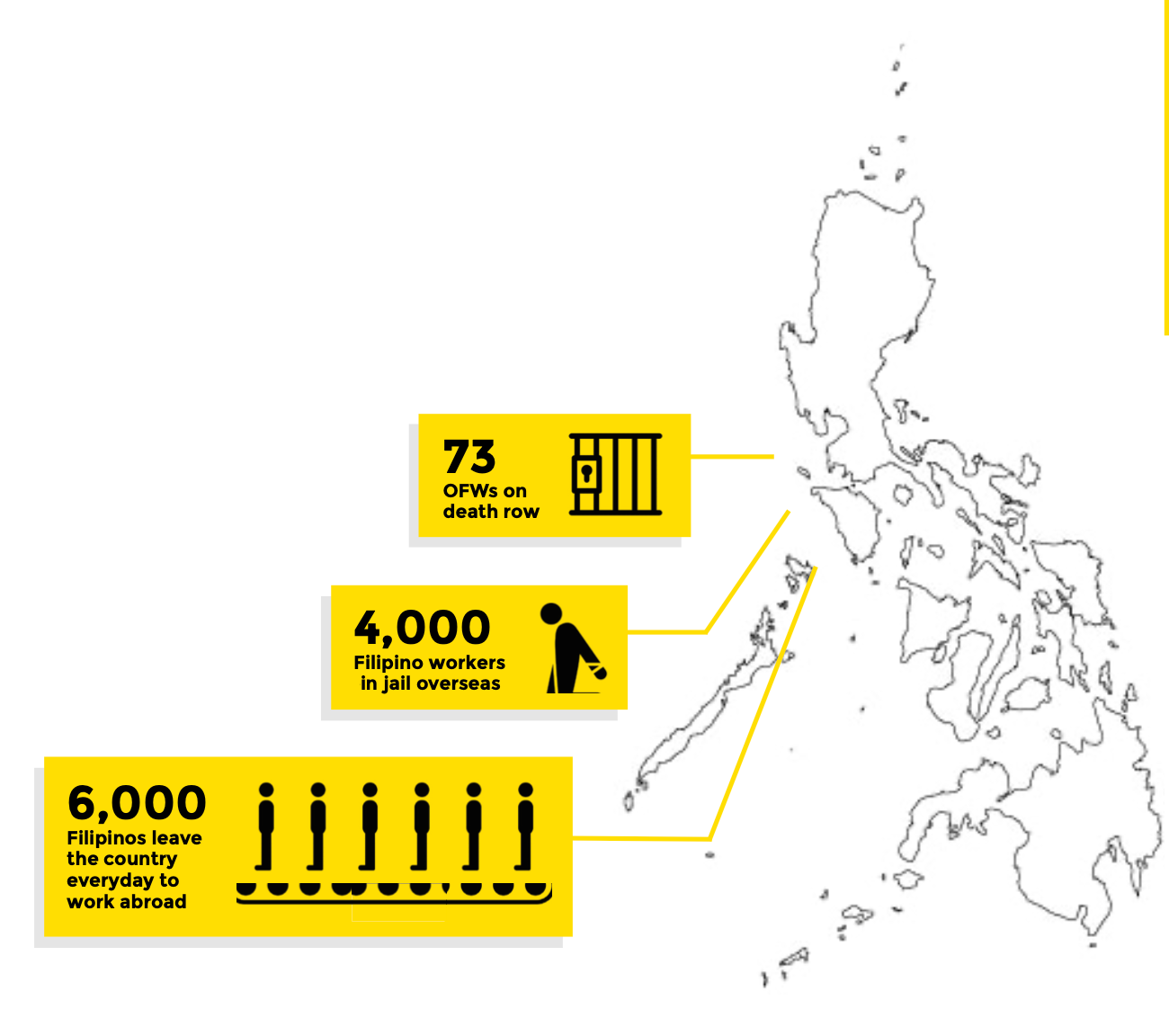

The stories of Elle and Lisa reveal that the outrageous negligence of the Philippine government and disservice to its citizens extend beyond the bounds of the country. With 4,000 Filipino workers in jail overseas, 73 on death row, and more than 6,000 Filipinos continuing to leave the country everyday to work abroad, Philippine governance in its current form is failing to meet the basic needs of its people. Instead, it has made way for the ongoing onslaught of attacks against the Filipino people and their aspirations for food, land, jobs, education, belonging and safety.

E: “My dream is very simple—to be reunited with my family who I’ve been separated from for a decade, on a small piece of land in a home all our own.”

These days, Elle and Lisa still work tirelessly to give a better future for their families back home in the Philippines. While they spend most of their week laboring in the mansions of wealthy Los Angelenos,on their days off,they traverse across the city by bus to neighborhoods populated with Filipino homes and turo turo style restaurants. They have found care and support in other

Filipinos who have also experienced the pains that come with forced migration, family separation, and exploitation. More and more, they realize that their life stories of perseverance and determination are a testament to the reality that ordinary people are capable of making great sacrifices and struggle to bring about extraordinary change. No longer do they carry their dreams of respect, dignity, genuine freedom and peace alone, but they share it with a community of Filipinos who, too, are striving and fighting for a better world.